Educator and author Mary Ellen Giacobbe lists three things necessary for all writers to be successful:

Time, audience, and choice.

It’s a damn good list.

But it’s missing one thing:

Purpose.

Writers need a reason to write. When writers see a grade as the only tangible endpoint to their work, we produce human beings who stop writing once school is finished. We also produce writers who are almost never enthusiastic about writing.

Purpose can come in many forms.

Purpose can come in the form of writing contests, complete with tangible, meaningful prizes. In addition to professional writing contests hosted by outside agencies, there are no fewer than five in-house writing contests running in my classroom at any one time. The topics vary. The judges are always rotating. And every contest culminates with a winner and a prize that means something to my students.

Students actually run their own writing contests in my classroom now, determining their own topics, judges, and criteria.

All of this is designed to offer an authentic, meaningful purpose for writing.

Purpose can also come in the form of publication or celebration of work, either in a tangible form or a public reading. Make a book. Print a weekly newspaper. Read before the class. Write and perform a monologue or comedy sketch. I have an enormous collection of puppets in my classroom for students who want to write puppet shows and perform for younger students. Provide a platform that means something to students and watch their love for writing blossom.

Purpose can also simply be be to make people laugh. Bring them closer to you. Find or strengthen friendships.

Write a joke. Write and tell a personal story. Share a little vulnerability with the class.

Every year I teach my students to use the power of the pen to rectify injustice.

Dissatisfied with service at a restaurant? Write a letter.

Unhappy with a school rule? Write a letter.

Desire a later bedtime? Write a letter?

Think I graded that assignment unfairly? Write a letter.

“Put that request in writing” is a constant refrain for almost every request in my classroom.

Last year, a student’s family received terrible service at a local Chilli’s restaurant. She wrote a letter to the company, describing the incident, and received $50 in gift cards and a note of apology. The year before that, a student wrote to a movie theater complaining about the usher’s failure to silence a group of teenagers during a recent visit. She received vouchers for 10 free tickets to future movies.

Can you imagine how those writers were feeling when those envelopes arrived in the mail?

When I was in high school, I started a business writing term papers for my classmates and was very successful, earning a sizable chunk of cash from classmates with no desire to write 25 pages on The Scarlet Letter.

I earned enough to purchase my first car: A 1978 Chevy Malibu.

I wrote letters to girls in attempts to woo them. Sometimes it worked.

I wrote for the school newspaper, in one case arguing the merit of a rule requiring me to type my papers but not allowing me to use school typewriters because I had never taken a typing class.

That rule was changed as a result of that article. The name of the piece was “The Right to Write.” I still have a copy of that newspaper today.

Most importantly, I saw writing as a possible doorway to the future. As a boy for whom the word “college” was never spoken by any adult in my life, I didn’t see much of a future for myself while in high school. Upon graduation, I was asked to leave my childhood home and earn my own living, absent any parental support.

College was something I dreamed of attending but never thought I would.

But maybe, I thought, I could write. In between shifts at the restaurant and scraping through life, maybe I could find a way to write something good, get noticed. and make something of myself. In the days before the internet, when the publishing world seemed impenetrable and opaque and I was young and alone, this was a bit of a pipe dream, but it was also my only dream.

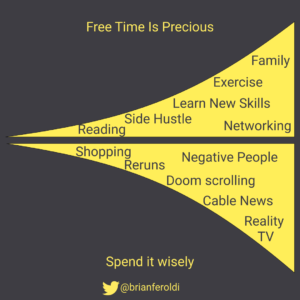

It represented purpose. It kept me writing. Every day. I wrote in journals. In a time before email or texting, I constantly wrote letters. I wrote short stories and poems. Jokes and sketches. On a localized bulletin board system – a precursor to the internet – my friend and I wrote a “He Said, He Said” column for an audience of a couple hundred users.

When my friend quit the column, I started writing both sides of every argument.

Once I finally got started, it took me three years to write my first novel. It took me less than a year to write my second.

Why?

Doubleday paid me for the first one. I received a check in the mail. Someone paid me for stuff that I invented in my head. I received a tangible, meaningful purpose to writing novels, so I starting writing more often. I dedicated myself to the craft. Carved out more time to make it happen.

It allowed Elysha to stay home for almost a decade to raise our children.

Purpose.

When a writer has a reason to write, they are far more likely to write. Far more likely to fall in love with writing. Far more likely to keep writing.

Don’t love writing? Find a purpose for your words, and I promise that enthusiasm will follow.

Teaching students who don’t love writing? Give them authentic, tangible reasons to write.

Not sure what those reasons could be? Ask them.