Vice President Kamala Harris could become the first U.S. President to have worked at McDonald’s. She worked under the Golden Arches for a summer while attending school.

It shouldn’t be surprising, given that 1 in 8 Americans have worked at McDonald’s at some point. Then again, most U.S. Presidents and presidential candidates tend not to emerge from the working class and fast food roots, so Harris’s election would really be something.

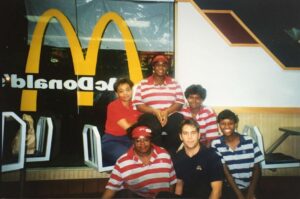

I started working for McDonald’s in the spring of 1987 as a junior in high school after my friend Danny told me they were paying $.4.65 per hour—ten cents more than the convenience store in our town. I was promoted to manager later that summer, and I worked nearly 40 hours per week during my senior year of high school, jamming ten-hour shifts into the weekends starting in the wee hours of the morning.

I worked for McDonald’s from 1987 through 1999, with two year-long interruptions when I went to work in banking and sales.

McDonald’s put me through college, allowing me to work a full-time, flexible schedule while also attending school full-time.

Not exactly an easy way to attend college — managing a restaurant full time while earning two degrees at two different schools simultaneously — but given that just before entering college, I had been homeless, jailed, the victim of a violent crime, and tried for a crime I did not commit, nothing seemed as hard.

I honestly felt blessed despite the outrageous, impossible workload.

McDonald’s also offered me extensive management training. It taught me many skills that have allowed me to succeed later in the classroom and in my businesses:

Delegation, organization, motivation, follow-up, cost-benefit analysis, customer service, and effective communication. My understanding of Mayo’s Human Relationship Theory and the scalar chain still inform my teaching today.

Understanding the Peter Principle has allowed me to avoid a career misstep and remain happy.

When I was 17, I was “calling the bin” on Saturday afternoons — a job that amounted to monitoring orders being placed at the counter and drive-thru and ordering food from the kitchen or “grill” based upon demand, anticipated demand and the need to keep waste as low as possible. It required understanding how every station in the restaurant worked so that you understood how long it might take to produce a run of Big Macs or McChickens. It required you to negotiate with the drive-thru staff — where more than half of all sales came — and cashiers, who faced scrutiny from customers standing before them, waiting for food. It required you to motivate kitchen staff, schedule breaks, and work as a cheerleader and taskmaster simultaneously. It forced you to process enormous amounts of information constantly and make critical decisions that determined service times, customer satisfaction, and profitability,

“Calling the bin” is a job that no longer exists. New processes have pushed it aside. But it was one of the most challenging jobs I’ve ever done. It prepared me well for managing a restaurant, a classroom, and, later, my businesses.

McDonald’s also allowed me to work with many different kinds of people.

In my first restaurant in Milford, Massachusetts, I managed people twice my age or more. In Brockton, Massachusetts, I was one of the only white people working in the restaurant. In Bourne, Massachusetts, many of my employees were teenagers, working on the Cape for the summer. In Hartford, Connecticut, most of my employees were immigrants from Peru, Mexico, and Central America who only spoke Spanish.

They taught me how to swear in Spanish.

The first person I hired was a formerly incarcerated man in a work release program.

He was also the first person I ever fired.

The first person I promoted to manager was a Chinese immigrant. When her mother arrived in America a year later, I hired her to make salads and do prep work.

I made my first Muslim friend while working at McDonald’s.

I made my first openly gay friend while working at McDonald’s.

I made my first Baháʼí friend while working at McDonald’s.

I made my first octogenarian friend while working at McDonald’s.

I made my first Jehovah’s Witnesses friends while working at McDonald’s, and they later rescued me from the streets.

While working in Hartford, I hired two high school dropouts and eventually convinced them to go back to school.

I met my best friend working at McDonald’s. He, too, was “calling the bin.” Ten years later, while I was still in college, still working for McDonald’s, still overwhelmed by work and school, we would somehow launch our wedding DJ company together.

It was another job that required us to process massive amounts of information quickly and make split-second decisions.

I’m confident our experience at McDonald’s helped.

Kamala Harris only spent a summer working for McDonald’s as a teenager, but I suspect she learned some skills during that short period. It likely reinforced her work ethic, introduced her to new and diverse people, and afforded her a window into the lives of people different from herself.

It’s happened before.

After selling his first company for $15 million, entrepreneur Scott Heiferman went to work for McDonald’s for a few weeks to reconnect with people.

He wrote:

“I spend a lot of time with bankers, lawyers, internet freaks, corporate wonks, and other people living strange lives. As a good marketing guy, that’s a bad thing. And as a practicing anti-consumerist, that’s a bad thing. I got a job at McDonald’s to help get back in touch with the real world.”

In writing about his time at McDonald’s, he said:

“Most of my McDonald’s co-workers did their jobs much better than I ever could. They just seemed quicker. They had various talents and intuition that I don’t have. I gained a bucket of respect for people that bust their butt for such low pay.”

It only took Heiferman a few weeks to gain that perspective.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Vice President Harris gained a similar perspective while working for McDonald’s.

Not a day goes by when a lesson I learned while managing McDonald’s restaurants does not help me in my work.

Perhaps Vice President Harris feels the same.