A new study shows that not everyone has an “inner voice” in their heads. The extent and intensity of that voice vary considerably from person to person, impacting how people think.

They found considerable differences, for example, in performance on given tasks, indicating that those with strong inner monologues are better at retaining and manipulating information with accuracy and rapidity.

My question:

Who doesn’t have an inner monologue?

I’m talking to myself constantly. I’m often talking to myself while I’m talking.

Years ago, I told a storytelling student—a doctor in the emergency department at Yale New Haven Hospital—that while I am telling a story, performing standup, or delivering a speech, I’m often talking to myself at the same time—monitoring audience reaction, adjusting content and delivery on the fly, and noting other things in the room.

She didn’t believe me. “You can’t be talking to yourself while talking to an audience.”

I assured her I was telling the truth and explained that as you grow more proficient at public speaking, you will require less bandwidth to do the job. At some point, you have enough bandwidth to both speak to audiences and yourself simultaneously.

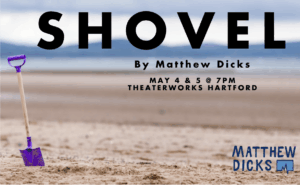

When I perform “Matt and Jeni Are Unprepared” — a storytelling improv show with my friend, Jeni Bonaldo—I constantly speak to myself because I am telling a brand new story in front of an audience without any preparation whatsoever.

The same is true when I perform standup. While I may have a plan when I take the stage, new ideas almost immediately materialize, and I need to decide which ideas make the cut and which should be avoided. That decision-making process happens while simultaneously trying like hell to be funny.

And I’m not a unicorn. I know other public speakers who report the same thing. While I suspect that many people who speak to audiences stick to the script and don’t possess this version of an inner monologue, those of us who spend enormous amounts of time onstage and speak for an hour or more probably do.

But my friend still didn’t believe me.

Two years later, she called me. “I can’t believe it,” she said. “I was just delivering a talk to my department, and I realized that while I was speaking, I was talking to myself. I even reordered a part of my talk midstream and debated with myself if it made sense.”

I then spoke four of my favorite words:

“I told you so.”

After two years of public speaking, she had reduced the bandwidth required to speak—including the nervousness that she felt while speaking—thus affording herself enough to engage in an inner monologue.

Yet, according to this recent research, some people have little or no inner monologue at all.

It’s hard to believe that, for some people, it’s just a vacuous, silent space between their ears.

No interior monologue.

No constant questioning.

No endless plotting.

But perhaps silence might also be a welcomed change for those with harsh inner critics. If you’re constantly beating yourself up, then silencing your inner critic might do you some good.

But because I understand the science behind the power of positive thinking and positive self-talk and leverage it whenever possible—which is to say almost always—my inner voice relentlessly compliments me, praises my every move, credits me for the smallest accomplishment, and constantly cheers me on.

It’s outrageous and ridiculous.

Loathsome, even, if you could hear it.

Happily, I possess an inner monologue.

Thankfully, I’m the only person who can hear it.