Writer Karen Attiah recently wrote about the pleasure of perusing other people’s personal libraries and then asked her followers about their “personal foundational texts.” — books that have impacted their lives.

I liked this idea a lot.

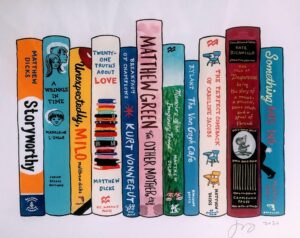

Here is my list:

“The Boy Scout Manual” — I have owned the Boy Scout Manual since childhood. This book taught me more about life and the essential skills required to be successful than any other textbook or book of nonfiction in my life.

“Breakfast of Champions” by Kurt Vonnegut — So much about Vonnegut informs my work today. His willingness to ignore convention and create a style entirely his own gave me permission to do the same. When Vonnegut steps into “Breakfast of Champions” as a character, my brain broke.

It was then that I understood I could do anything with my writing.

“The Dark Tower” series by Stephen King — Stephen King also steps into his Dark Tower series as a character, but he takes it one step further. He uses a real-life incident from his life brilliantly and unforgettably to pivot the story on its head. But more than that, it’s the way King weaves genres across this series of books — western, science fiction, and horror — and the way he creates mythology, culture, language, and religion that have brought me back to this series again and again.

It’s also remarkable storytelling with four of the finest characters in all of literature. It was these books that taught me to place character first and always.

“Diary of a Young Girl” by Anne Frank — I first listened to this book on cassette tape, so when the cassette ran out, I went to the box for another and discovered it was not there. Anne Frank’s book ends because evil men murdered her mid-story. It’s a book that serves as a reminder that time is fleeting, authors die, genius is ultimately extinguished, and my lifelong, relentless pursuit of applying words to the page is both warranted and advised.

“The Dungeon Master’s Guide” — I began writing my first real stories as a Dungeon Master for my teenage friends, and this book taught me that everything is ultimately structure. If you want your story to sing, you must be able to see its structure. Revision cannot happen in a series of sentences. Instead, you must see your story comprised as components of a larger piece.

The Dungeon Master’s Guide taught me this.

“Elements of Style” by Strunk and White — I carry this book’s straightforward, essential lessons in every sentence I write. It is a brilliant dissertation on the use of the English language, and it resides in my backpack, ready for review at all times.

“The Gospel of the Flying Spaghetti Monster” by Bobby Henderson — This book taught me that criticism can come in the form of creation.

Do you want to point out that every religion is just a bunch of stuff spoken by people about a supposed God?

You can criticize and make fun of religion, or you can invent your own religion with your own spaghetti-based God and honest-to-goodness philosophy and sell millions of copies of your religious tome as a means of saying the same thing.

“Macbeth” by William Shakespeare — I fell in love with Shakespeare through this story first. Once you know Shakespeare, you see it everywhere: in quotes, echoes, and themes. You become someone “in the know.” You see literature and theater and advertising and comedy and comics differently forever. These remarkable stories were written by a remarkable storyteller who taught me the value of stakes, suspense, surprise, and humor.

“Made To Stick” by Chip and Dan Heath — This is the best book on teaching and communicating that exists. Every teacher should read it. Storytellers, too. I read it at least once per year (and am reading it right now), and though anecdotes about folks like Lance Armstrong haven’t aged well, the lessons are just as relevant today as they were when I first read this book two decades ago.

“The Pleasure of My Company” by Steve Martin — While struggling to write my first novel, I stumbled upon this remarkable by the great Steve Martin. It’s the story of a man suffering from chronic obsessive-compulsive disorder. Though the novel has a plot, the primary focus of the story is on the character and how he struggles to maintain a life enveloped by artificial obstacles.

After reading this book, I understood that a protagonist’s inner life is far more interesting than anything they might say or do and that courage is defined not only by a person’s actions but also by the willingness to be oneself in a world that demands something more.

When people ask me for a unifying theme in all of my novels, this is essential what I say:

I’m fascinated by people who possess the courage to be themselves in a world that does not appreciate or accept them for who they really are. It all began with the reading of this slender novel written by a comedian who I have admired all my life.