My friend, Tom, watched this TED Talk and thought of me.

The talk centers on what the Rufus Griscom and Alisa Volkman call “the four taboos of parenting.”

One deals with the propensity of women to avoid speaking about their miscarriages.

With no experience in this realm, I will refrain from commenting on this one.

The remaining three are:

You can’t say that you didn’t immediately love your baby.

As Tom said when he brought this to my attention:

“You’ve been saying that ever since Clara was born!”

It’s true. I loved Clara when she was born, but in comparison to how I feel about her today, I barely loved her.

I marginally loved her.

I probably loved her as much as I love ice cream cake and the New England Patriots.

I loved her because I was expected to love her.

I was also hungry when Clara was born, which isn’t an excuse for not loving your newborn daughter enough except it is.

I was really, really hungry.

I hadn’t eaten in almost eighteen hours, and I had barely slept the night before. Clara would not stop crying. After extracting her from my wife via cesarean section, a nurse placed her in my arms and abandoned me. While she counted sponges and sutures and instruments for the next hour, I was stuck holding this screaming newborn.

In all of the useless childbirth classes that I was forced to endure, this important fact was left out:

It only takes about ten minutes to extract a baby via c-section, but it takes more than an hour to put the woman back together again.

And I was hungry, damn it. So how could I have been expected to love Clara in the profound and moving way that most people claim?

I just wanted a burger.

Besides, men are different than women. We are less capable of unconditional love. It became much easier to love Clara once she started loving me.

It may be taboo to say that you didn’t love your child very much when he or she was born, but I have been saying it for two years, as Tom can readily attest.

The remaining two taboos are:

You can’t talk about how lonely having a baby can be.

You can’t say that your average level of happiness has declined since your baby was born.

According to Griscom and Volkman, as taboo as they might be, both of these statements are generally true, and they cite the following statistics in support of their assertions:

58% of new mothers express a feeling of loneliness following the birth of their baby.

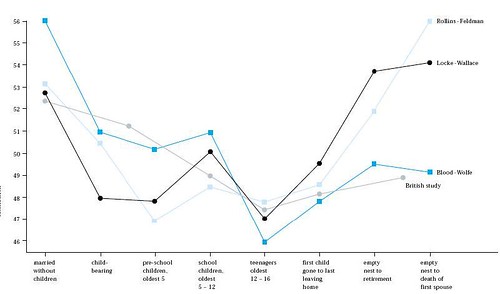

The average degree of martial satisfaction declines precipitously following the birth of a child and only rises after the child has gone off to college, as shown in this chart:

These admittedly compelling statistics lead Griscom and Volkman to assert that candor and brutal honesty are critical to successful parenting. They believe that soon-to-be parents need to be made aware of these unfortunate facts of life so that they can be better prepared for what lies ahead and establish reasonable expectations prior to the birth of their child.

I agree, except for one important caveat:

Whenever I dispense advice or information based upon statistical evidence, I always take the bell curve into consideration.

For example, although 58% of women report increased loneliness following the birth of their first child, 42% do not.

42% is a big number.

So when I am speaking to a new mother, I attempt to fix her position on the bell curve before choosing what to say.

I ask myself:

- Is this person of average, above average or below average intelligence?

- Is this person in a healthy, loving relationship?

- Does this person possess a reasonable degree of perspective on life?

- Is this a person who tackles challenges effectively?

- What is the quality of the person’s overall life?

Only then do I proceed.

If I am faced with a generally dissatisfied, unskilled basket case, then yes, I would probably let her know about the 58% of women who experience loneliness following childbirth, because she is more likely to fall into this category.

But if I am speaking to a smart, organized, emotionally stable problem solver with a strong support system, I would be much less likely to warn her about the possibility of postpartum loneliness.

It’s simply less likely that she will experience it.

This is not to say that there is anything wrong with a woman who feels lonely after childbirth. I simply have no desire to pass on depressing news and would prefer to err on the side of optimism.

The same applies to the statistics regarding martial satisfaction. Though the chart above is compelling, there is an invisible chart lying just behind it that illustrates the minority of couples who did not fit the line graph (and those who exceed it).

Again, the bell curve is at work here.

So when my friend, Jeff, asked me about the trials and tribulations of becoming a parent, I told him to ignore the naysayers and their doomsday warnings because Jeff consistently operates on the far end of the bell curve in almost all regards (excluding height).

He’s a smart, capable, successful, well rounded guy in a great marriage. I told him that my happiness has only increased with the birth of my daughter and that parenting is not as difficult as so many claim.

I expected Jeff to handle parenting masterfully, and I told him as much.

And he has.

A good rule of thumb (and perhaps an entry into Bartlett’s someday?):

Average is only applicable if you are average.