A report on the possibility that “parental happiness is a psychological defense—a fiction we imagine to make all the hard stuff acceptable” opens with the following paragraph:

Raising children is hard, and any parent who says differently is lying. Parenting is emotionally and intellectually draining, and it often requires professional sacrifice and serious financial hardship. Kids are needy and demanding from the moment of their birth to . . . well, forever.

I can’t tell you how much this annoys me.

Beginning with the moment that Elysha became pregnant, scores of parents have seemed hell bent on telling us how difficult and dreadful parenting would be. They inundated us in the stories of sleepless nights and terrible toddlers and rampaging teenagers, as if doing so somehow unburdened them of their own parenting woes.

Clara is now two years old, and so far these prognostication have proven to be unfounded, as has the first paragraph of the Association for Psychological Science’s report, which calls me a liar for stating otherwise.

“Raising children is hard,” the report claims.

This is not how I would characterize my experience as a father thus far. And it is not how I would have characterized the ten years I spent as the step-father to a girl ages 6-17. I have endured hardships throughout my life. Honest-to-goodness calamities and years of seemingly unending misery.

Nothing about my daughter has compared.

“Parenting is emotionally and intellectually draining,” the report claims.

While parenting can be emotionally and intellectually demanding at times, it has hardly been draining. It is not close to draining. It is not in the same universe as draining.

“…it often requires professional sacrifice and serious financial hardship,” the report claims.

I have experienced serious financial hardship. I grew up in the teeth of financial hardship. I wore hand-me-down canvas sneaker for entire winters and was hungry for much of my childhood. Having to manage our household budget on less money than we are accustomed can be exceptionally difficult at times, but I am not living in my car (as I once did) or sharing a room off the kitchen with a goat in the home of a family of Born Again Christians (as I also did).

And “professional sacrifice?”

I’ve continue to teach at what I consider a equally high level of skill. Actually, I think that having a daughter has made me a better teacher. I have a greater understanding of a parent’s point of view, and I think this has allowed me to forge more meaningful relationships with the parents of my students.

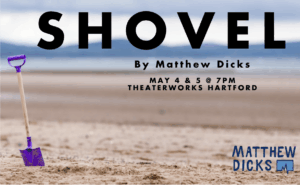

I’ve also written four novels, continued to run a small business and launched a career as a storyteller in the time that my wife first became pregnant.

Some may say that my wife has made a professional sacrifice by staying home with our daughter for her first eighteen months, but I think my wife would say otherwise. She has returned to work in a position that makes her extremely happy and is positioning herself to assume an even more appealing position once we’re done having babies and they are all off to preschool.

Having a child will ultimately assist my wife in transforming her career into something new and exciting, and when she returns to work full time, she will be happier than she has ever been.

“Kids are needy and demanding from the moment of their birth to . . . well, forever,” the report claims.

This is simply not how I would characterize my daughter. In fact, in the last thirty minutes that I have spent writing this post, Clara has been playing with blocks in the other room. I have wiped her snotty nose twice, helped her open the bag of blocks, and only been distracted in order to watch her build towers.

Sometimes I can’t resist. She’s too damn cute.

See where she was sitting?

Clara brings me so much joy that to characterize her as needy or demanding would be absurd. For every diaper that needs changing or every nose that needs wiping are more than enough moments of happiness and fun to tip the scales well in my favor.

The researchers might say that I am suffering from “cognitive dissonance”—the psychological mechanism we all use to justify our choices and beliefs and preserve our self-esteem.

I would say that not all parents are alike. Not all kids are alike.

Perhaps the fact that my wife and I are both teachers with more than 25 years of combined experience in educating children has made a difference.

Maybe our relative lack of materialism has allowed us to deal with the financial constraints better than some.

Perhaps the presence of exceptional friends and family has made child-rearing much easier by providing us with a wealth of experience and knowledge from which to draw.

Maybe my previous parenting experience has played an important role.

Maybe the strength of our marriage had helped us to work together better than some.

Maybe Clara is simply an easy, happy, compliant child and we are damn lucky.

Regardless of what factors have played a role, parenting for us has not been hard, and my reaction to this piece would have been considerably less visceral had the author, Wray Herbert, left out the line implying that to state otherwise makes me a liar.

Perhaps Herbert is engaging in his own brand of cognitive dissonance, blind to the reality that not all parents and children fall into the neat and organized categories that he would like.