The 5 rules of punishing children

Back in 2017, a judge in Hawaii ordered a defendant to write more than 140 “nice” things about his ex-girlfriend after he violated a protection order.

“For every nasty thing you said about her, you’re going to say a nice thing,” 2nd Circuit Judge Rhonda Loo told Daren Young. “No repeating words.”

Young was ordered to stop contacting his ex. But two months later, he called and texted her 144 times over the span of about three hours. As a result, he was arrested and spent 157 days in jail.

Young was also placed on two years of probation fined $2,400, and assigned 200 hours of community service.

Then the judge gave him the writing assignment.

Four years ago, I punished a student for not completing her homework by assigning her weekend homework:

Knowing that she and her sister fought all the time, I required my student to write 100 loveable things about her sister. Then I framed the list of compliments and passed it onto the sister.

Her parents thought the punishment was hilarious. So, too, did our class.

My student was not initially amused, but the story of the punishment became part of the classroom lore, and she was eventually able to tell the story and laugh at herself. She has even visited the class from time to time over the years and told the story to my latest batch of students.

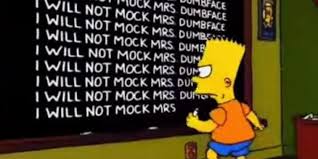

I have assigned many consequences like this over the years. Novel, amusing, unusual, personalized consequences for students failing to follow the rules.

I have five rules about imposing consequences on students:

- The student can’t hate school as a result of the consequence.

- The best consequence is specific to the needs, wants, and preferences of the student.

- Waiting to discover what the consequence will be should be part of the consequence.

- Whenever possible (and therefore almost always), I impose the consequence. Involving the principal in classroom discipline undermines my authority and makes me second fiddle.

- Consequences must be unpredictable.

That last one is extremely important. As a kindergartener, I realized rather quickly (and perhaps disturbingly so) that punishment was simply an exchange of time for freedom:

If I want to finish building my tower of blocks after Mrs. Dubois has told me to put the blocks away, I must trade 15 minutes in the corner for that freedom.

I could do that time. That was a solid trade.

Eventually this understanding led to decisions like:

I want to sneak into the rafters of the auditorium during study hall with Derek Reynolds so we can explore the heating and cooling conduits of the school and eventually find our way onto the roof?

I’ll need to trade 2-4 hours of after school detention, spent reading and completing homework, and only if we are caught.

Deal.

We never got caught.

When students see punishment as the ability to make a choice not normally allowed in exchange for a predictable amount of time, they will begin to make those calculations and strategically choose when misbehaving makes the most sense.

Not all students, of course. The majority of students want to follow the rules. Even when they don’t, they are rarely violating rules strategically. They are are simply making mistakes, blundering into trouble, and executing regrettable decisions.

But these kinds of students don’t pose problems for teachers. These are not your chronic offenders. It’s the students who understand how to game the system who can make a teacher’s life difficult. The students who do not fear authority. The last thing you wanted was for a student like me to accurately predict the punishment for every infraction.

When the consequences are unpredictable, unknown, and novel, kids like me are less likely to take those chances and more likely to behave.

Of course, the best way to get kids to behave is to set clear expectations, allow your students realize success on a daily basis, let them know unequivocally that you love them, and for God’s sake, make school fun.

If you do that, most of your problems disappear.