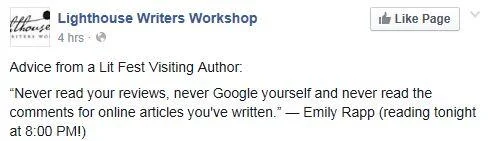

As an author, I have often been told that it is a bad idea to read my reviews.

Advice like this is quite common:

Simply Google the words “Never read your reviews” and you’ll find an endless list of posts from writers and the like explaining why they never read their reviews:

I think this advice is ridiculous.

Unless you truly don’t care if your books are ever sold or read, how could avoiding your reviews possibly help your effort to sell books?

As crass as this may sound to some, the responsibility of a author goes far beyond the application of words to a page. Writers are also business people. Salespeople. Advertisers. Marketers. Brand builders.

It is our job to help our books find a way into the hands of readers.

It’s our job to write and sell books.

One of the tools that we have to assist in this process is customer feedback. Whether this comes in the form of a review published in a magazine or newspaper or a customer rating on Amazon, all of this data is valuable to the author if he or she can stand a little criticism.

In what other business would the creator of a product ignore the feedback from the customers?

When my first novel, Something Missing, published back in 2009, I read the reviews. Admittedly, they were good. The book was reviewed well in newspapers and trade publications, and it averages 4.3 out of 5 stars on Amazon.

Still, there was information to be gleaned from both the positive and negative reviews.

Primarily, I learned that the books starts out slowly. Even positive reviews comments on the importance of sticking with the story. Allowing it to develop. Waiting for the ball to get rolling. Thanks to my agent, I already knew this might be a problem, but reading reviews from readers helped to cement this notion in my mind.

I needed to get my story moving quicker in my next book.

My next book, Unexpectedly, Milo, was also reviewed well. Again, it averages 4.3 out of five stars on Amazon, and the newspapers and trades liked the book, too.

But once again, negative comments centers on how the plot takes a while to get moving. Again, even positive reviewers advised would-be readers to “give this book a chance” and “just wait because as soon as the plot gets rolling, it never stops.”

I hadn’t learned my lesson. I vowed to do better on the next book.

And I did. Memoirs of an Imaginary Friend has been my best reviewed book to date, both in the press as well as by readers. Critiques often centered on the simplicity and repetitive nature of the text, but these elements were intentional. The story is being told by a five year-old imaginary friend.

Gone were critiques on slow moving plots.

I learned to launch my stories closer to the inciting incident. I learned that shorter chapters make the reader feel like the book is moving along quickly. I learned that the methodical process of meeting the character and discovering his or her world before allowing the plot to take off is not how people enjoy reading stories.

It’s not how I enjoy reading stories.

I learned all of this by reading my reviews.

Writers cannot afford to be so fragile as to avoid reviews. They must learn not to take individual reviews personally, but they must also be on the hunt for patterns in the thoughts and critiques of their readers.

We don’t write books in a vacuum. You don’t write books for ourselves. We write books with the hopes that readers will find, read, and love our stories, which means we must be willing to listen to our readers. Find out what they think. Apply those lessons to future stories.