I’m known to have a limited palate. It’s not as limited as many of my friends contend, but there are admittedly large numbers of foods that I do not like, including salad, a great number of vegetables, many nuts, most Asian cuisines, most sauces and dressings, and more. I also don’t drink coffee or alcohol.

People have many theories on my limited palate. People like to express these theories to me often.

I have many theories on their more expansive palates, including the belief (backed by science) that we have little control over the foods that we find palatable, so shaming, harassing, or otherwise disparaging a person’s food preferences is insensitive and stupid.

My friend actually purchased a testing kit and confirmed that I am a supertaster, which means that I taste more flavors – and am therefore sensitive to more flavors – than the average person, which goes a long way to explaining my limited palate.

I am tasting all the awful flavors that your less effective taste buds are missing.

Recently, Paul Rozin, a cultural psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania, has added to the research on food preferences. Rozin is especially interested in why people learn to love foods they initially hated, a phenomenon he calls “benign masochism.”

He has come up with two reasons to explain how this happens:

- Repeated exposure

- Social pressure

This explain a lot in terms of my limited palate.

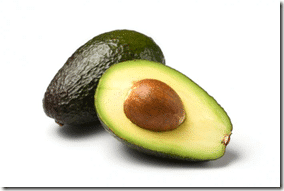

Repeated exposure means that in order to learn to like a food that I don’t – say avocado – I would have to suffer again and again until I theoretically began liking it.

This sounds insane. I have to eat a food that I can barely swallow without feeling ill or vomiting in order to expand my palate? There are far too many palatable foods in the world for me to spend time torturing myself over a food item that doesn’t even grow naturally where I live.

But it’s the aspect of social pressure that perhaps explains my palate best. I am and have always been a nonconformist in the most extreme sense of the word. Social pressures have never meant all that much to me, oftentimes to my detriment. The thought that I might eat a food that I consider unpalatable in order to better align myself with the people around me sounds ridiculous.

Then again, I am often sitting at the table in a restaurant, staring at people who are enjoying the salad course while I gnaw on a piece of bread and politely readjust my napkin on my lap.

This doesn’t bother me, but perhaps it would make most people uncomfortable.

Maybe it’s a person’s desire to join his friends for sushi after work on Fridays that causes him to find a way to enjoy eating something that should obviously be cooked before eating.

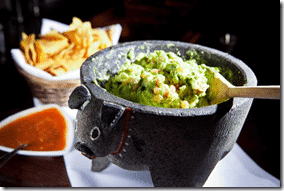

Maybe it’s the incessant fawning over guacamole – made right at the table! – that pushes the avocado hater over to the dark side and decide to dip a chip.

Maybe it’s the pervasive, inexpensive nature of salad that causes so many people to adopt the dietary habits of small woodland creatures.

Rozin’s theory makes sense. If social pressures cause people to walk around with brand names plastered to their clothing and handbags and somehow think this is a good thing, then why would this not also apply to foods that initially make us feel ill?

Rozin also coins the term “hedonistic reversal” – the ability of our brain to tell our senses we’re going to turn something we should avoid into a preference. This applies to the person who decides that the spiciest buffalo wings are his favorite, mostly because he has become convinced that eating foods that most people find unpalatable makes him feel superior.

You know the type. These are the people who eat eye of newt because it’s the newest, latest food trend, and they want to appear cutting edge. Hip. Brave.

They never do. Instead, they often appear cloying. Desperate. Sad.

I’m not that kind of person, either. I hope.